Global Inequality

There are two ways to conquer and enslave a nation. One is by the sword. The other is by debt. – John Adam

Global inequality is a concern that is increasingly taking center stage. Schools around the world teach about colonialism, the slave trade, and wars like the Opium War aimed at opening markets. However, what has transpired in the past few decades is often left uncovered.

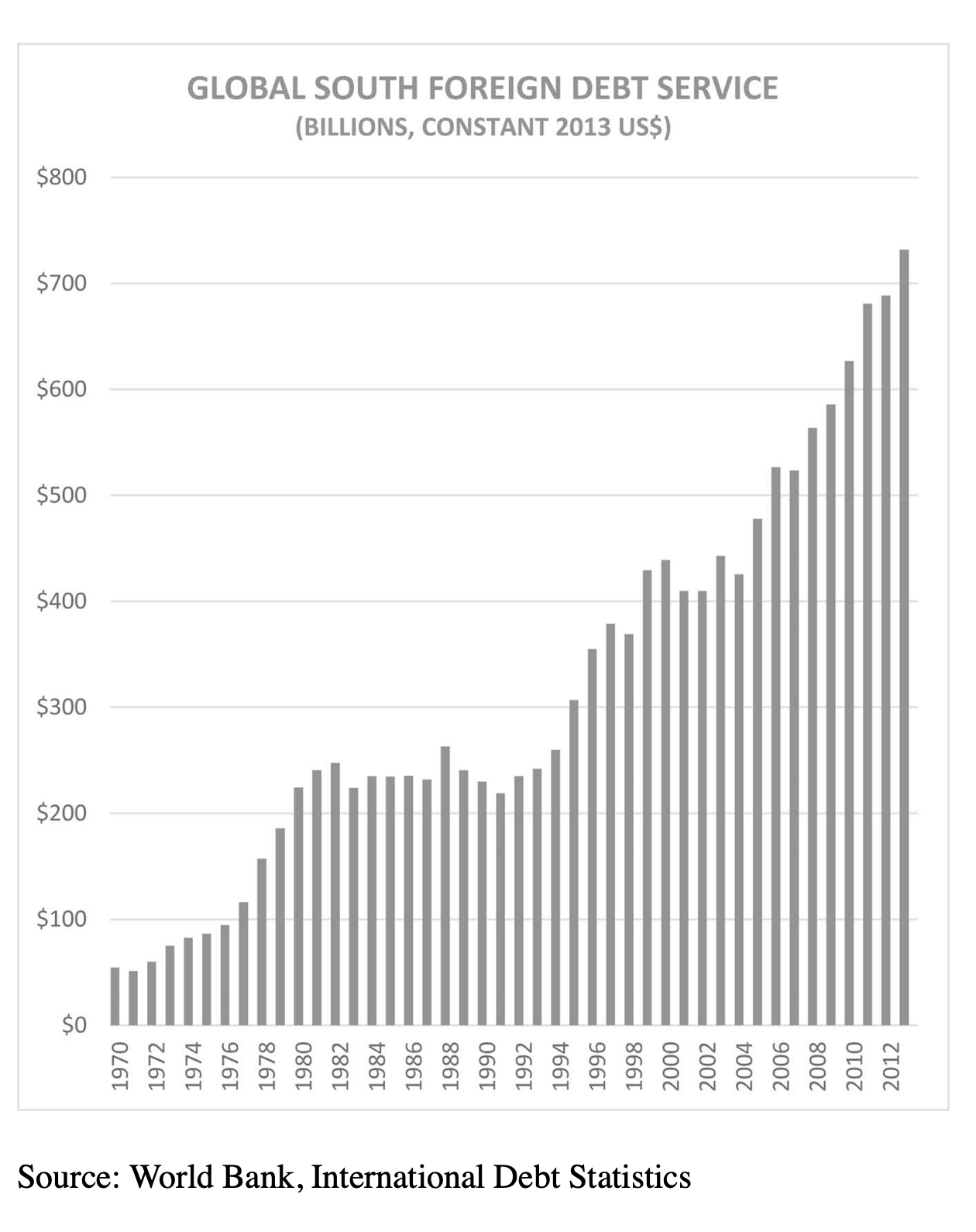

In the 1970s, newly independent countries in the Global South were in dire need of capital to develop their economies and implement import-substitution industrialization. Wall Street banks were quick to lend the necessary funds, operating under the assumption that governments would be unlikely to default. Yet, this created a global sub-prime market. High inflation rates in Western countries made trade difficult and debt repayment even more challenging for these nations. The bubble burst when the U.S. Federal Reserve raised interest rates to 21%. Mexico was the first to default on its debt in 1982, triggering similar defaults by Brazil and Argentina in what became known as the Third World Debt Crisis.

Rather than absorbing the losses, banks turned to the U.S. government for assistance. The IMF was then repurposed to help these banks recover their loans. Originally designed by by John Maynard Keynes to sustain government spending and prevent depression, the IMF was now used to enforce austerity, privatization, and market liberalization on the debtor nations and banks.

The conditions were as follows:

- Austerity: Reduced spending on public services like hospitals and education and subsidies to local industries to make room for debt repayments, which makes harder for local people to learn skills needed and local industry to grow.

- Privatization: Selling off state-owned enterprises, which often led to increased costs that burdened the poor.

- Liberalization: Radical deregulation of the economy, the removal of trade barriers, the opening of markets to foreign competition and abolishing capital tariffs.

These policies are purposed for the developing countries to repay the debt to the western banks, but they are were counterproductive for nations freshly emerged from colonial rule and in need of economic nurturing. What’s more, because these loans were denominated in U.S. dollars, debtor nations couldn’t use inflation or monetary expansion as tools for growth and employment—options that would have otherwise been available for debt managed in their own currencies.

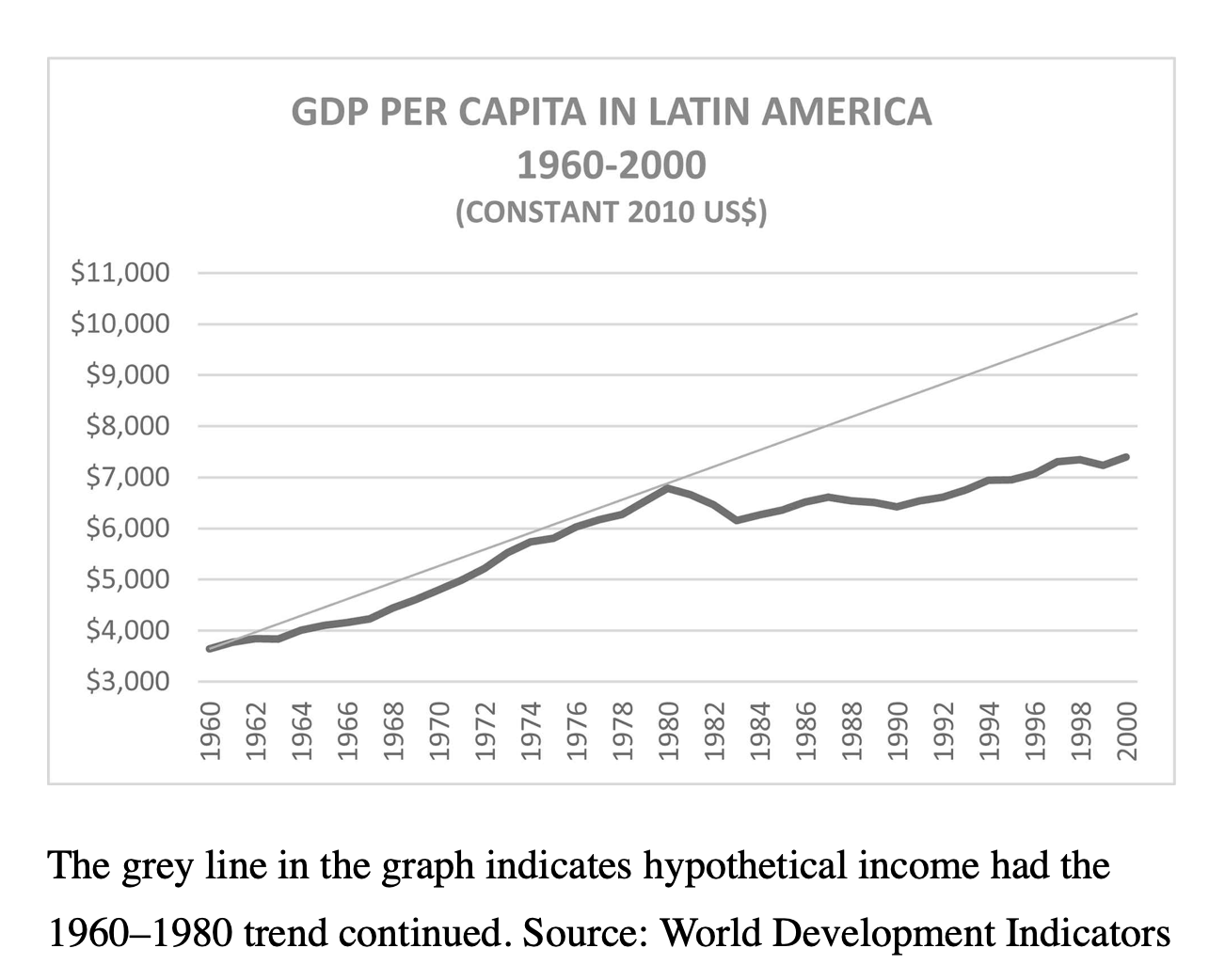

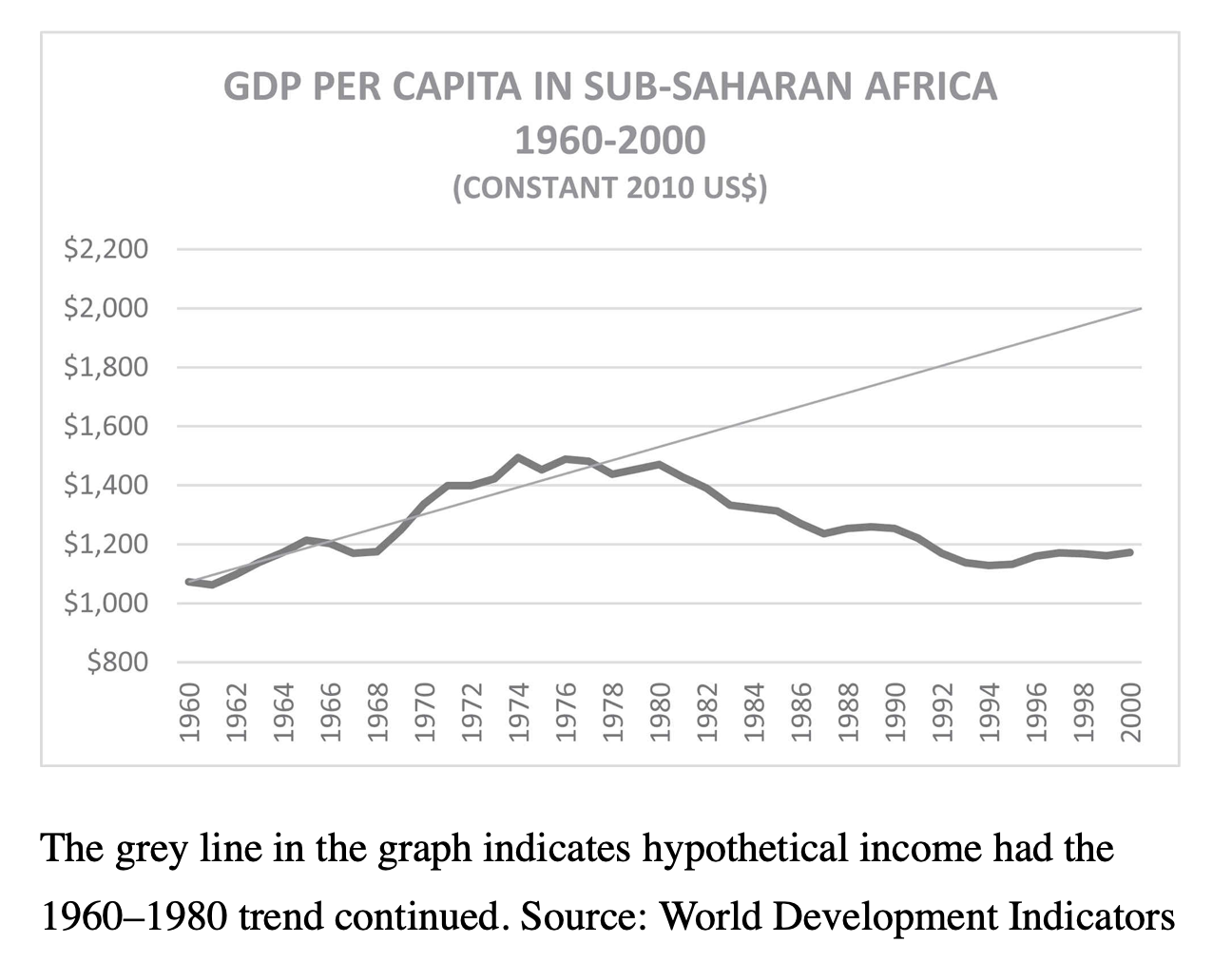

While the IMF was taking these steps, the World Bank also imposed similar conditions known as structural adjustments. Both organizations promised that these measures would spur economic growth and reduce poverty. However, the outcome was quite the opposite.

China stands as an outlier in this discussion. During its period of rapid economic growth, China largely rejected the previously mentioned financial conditions set forth by the IMF and the World Bank. China’s ability to do so rested on a unique set of advantages not universally available to other developing nations. These advantages include a strong central government, a sufficiently large domestic market for its goods, and a network of overseas Chinese investors willing to invest in the country, thereby reducing the need to take on foreign-currency debt.

The book “The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions” by Jason Hickel discusses much of this, particularly in its third chapter. Yet, two issues need further examination:

-

The Real Beneficiaries: Is it accurate to frame the issue as global south (or developing countries) vs developed countries? While the policies of privatization and liberalization have opened lucrative avenues for investors and multinationals from the developed world, the benefits don’t seem to trickle down to the average citizens in these wealthy nations. As Michael Pettis has argued in “Trade Wars Are Class Wars,” it’s actually the working class and the impoverished across the globe who bear the brunt of these economic policies. Meanwhile, elites in both developed and developing countries reap the rewards.

-

The Feasibility of Debt Relief: Some experts, including anthropologist David Graeber, advocate for debt relief as the way forward. While the idea is appealing, it seems unrealistic in practice. Defaulting on international debt would likely lead to a country being ostracized from the global financial system, with catastrophic economic consequences. It is not feasible unless some fundamental changes happened in the current system. For a more sustainable solution, there needs to be a competing financial framework, one that operates independently of the existing system.