Europe's Lesson

This post serves as a continuation of our previous discussion “Japan’s Lesson”. Today, we’ll dive into understanding the economy of Europe over the past two decades through the lens of balance sheet recessions.

To grasp the complexities of Europe’s economy, it’s crucial to understand the mechanics of its monetary and fiscal policies. Countries within the Eurozone utilize the common currency - the Euro. The European Central Bank (ECB) was established to govern the monetary policies of Eurozone countries, which influence the interest rates on the Euro. Conversely, each country has the authority to set its own fiscal policies and goals, albeit with certain constraints.

According to the Maastricht Treaty, EU member nations are required to limit their fiscal deficit to 3 percent of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This cap is implemented to prevent Eurozone governments from accumulating large budget deficits, which could potentially undermine the credibility and value of the artificially created Euro. However, such a cap can create serious problems during a balance sheet recession.

With this context in mind, let’s go back in time to Germany in 2000.

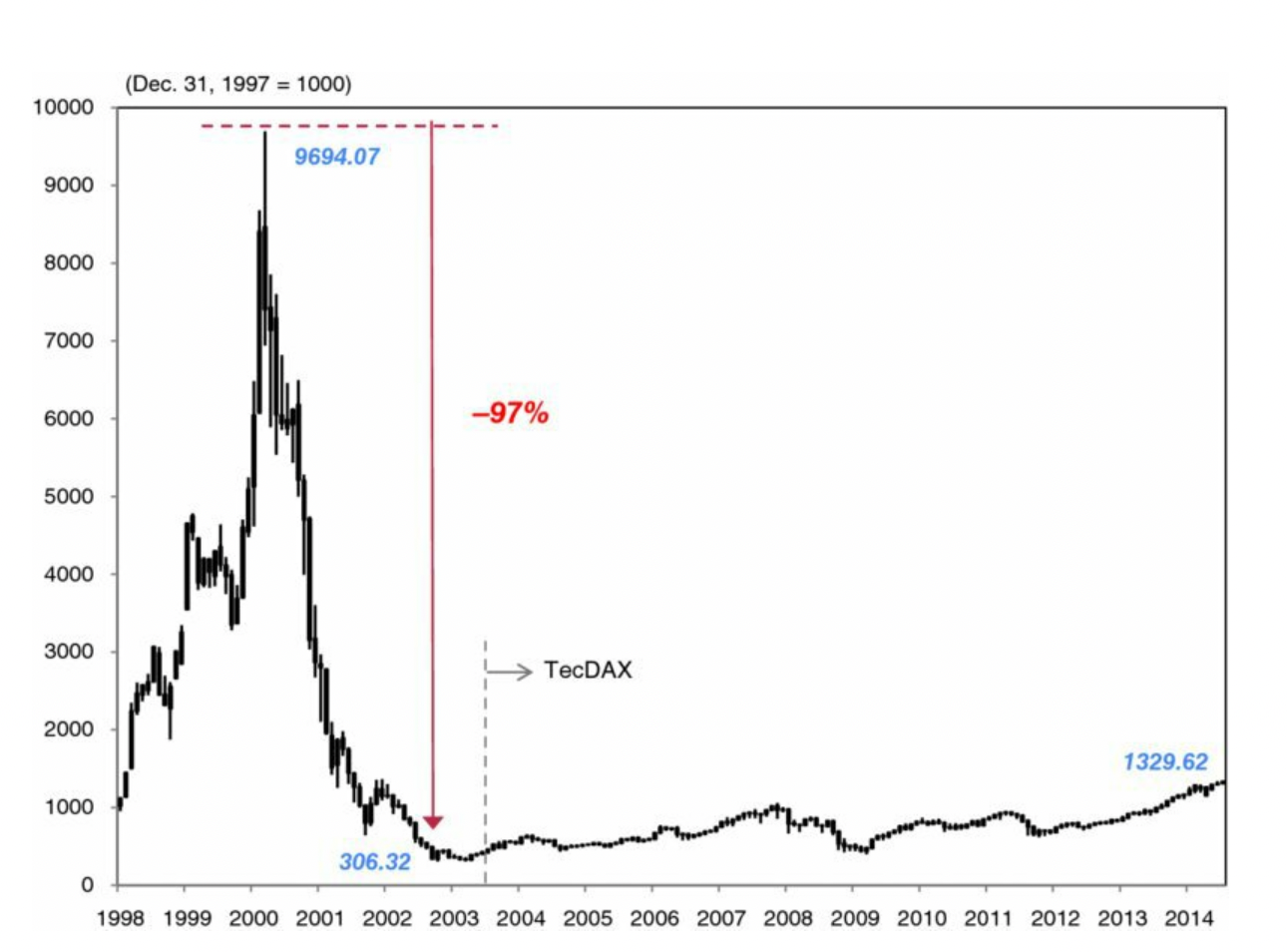

(Neuer Markt Collapse in 2001 Plunged Germany into Balance Sheet Recession. Source: Bloomberg, as of July 4, 2014)

(Neuer Markt Collapse in 2001 Plunged Germany into Balance Sheet Recession. Source: Bloomberg, as of July 4, 2014)

After the internet bubble burst in 2000, Germany found itself in the throes of a severe balance sheet recession. German households began to drastically increase their savings and ceased borrowing, focusing solely on paying off the debt accumulated during the bubble era. This situation closely mirrors Japan’s economic scenario in the 1990s. The most effective policy solution in such a case would be for the government to intervene and begin borrowing. However, the Maastricht Treaty restricts such actions. In an attempt to lift Germany out of this recession, the ECB aggressively cut interest rates to a post-war low of 2 percent by 2003. Nevertheless, the private sectors remained resistant to borrowing.

While Germany was still grappling with significant debt, peripheral nations not involved in the internet bubble saw the ultra-low interest rates as an opportunity to invest in real estate. Concurrently, German banks, with vast sums of unborrowed savings, began lending to these peripheral countries, leading to an overheating of their real estate markets. This European housing bubble mirrors the US housing bubble, triggered when the Federal Reserve lowered the interest rate to a post-war low of 1 percent following the US internet bubble. German banks even purchased collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) from US subprime loans to lend out their unborrowed savings, leading to substantial issues when the housing bubble burst in both the US and Europe. If the German government had been allowed to run a deficit exceeding 3 percent, many subsequent issues could have been avoided.

Another complication for Europe, beyond the Maastricht Treaty, arises when investors can purchase other countries’ government bonds without currency risk. During a balance sheet recession, unborrowed savings often gravitate towards government bonds because the government becomes the only borrower during that period. Although looking overseas is an option for investors, it involves a currency risk as liabilities will be entirely denominated in the local currency. This risk causes government bond yields in countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan to drop significantly during balance sheet recessions, providing these countries with much-needed fiscal space. Unfortunately, this is not the case in Europe. Investors within countries experiencing a balance sheet recession can simply invest their money in other Eurozone countries, all of which use the same currency. This prevents local government bond yields from dropping, leaving the government with no fiscal space.

To address the aforementioned issue, some have proposed Eurobonds, a way for the Eurozone to unify both monetary and fiscal policies. Although this solves the problem by consolidating 17 separate government bond markets into a single one, it presents various political issues related to debt issuance and allocation. Furthermore, a common fiscal policy might not suit countries with economic cycles that are out of sync, making it even more challenging to implement from a political perspective.

To rectify this capital flow issue, the author proposes two solutions. The first, albeit idealistic, is a rule barring Eurozone governments from issuing debt to anyone other than their own citizens. Although potentially effective, this solution could be challenging to put into practice. The second proposal involves maintaining a low-risk weight for domestic government bonds, while significantly increasing the weight assigned to bonds from other governments. This approach is based on the principle that financial institutions should set aside more capital against riskier loans or investments, and the assumption that domestic investors have the best understanding of the local economy and bond market. The second option is more feasible, given that risk weights already play a key role in financial regulatory efforts globally.

In conclusion, the author suggests two structural defects within the Eurozone need rectification: 1) The Maastricht Treaty, which doesn’t allow governments to borrow more than 3 percent during a balance sheet recession, and 2) the destabilizing flow of capital between various government bond markets within the Eurozone. Correcting these flaws would prevent distortions in monetary policy by freeing the ECB from the burden of a disproportionately broad role in rescuing countries in the grip of balance sheet recessions.